The Pros and Cons of Filmmaking as Research

StoryLab / Sheffield Documentary Film Festival, 9-12th June 2018

Supported by StoryLab and Sheffield Documentary Film Festival, a panel of filmmakers and academics explored the growing trend of straddling filmmaking and academic lives and discuss the pros and cons of making films as research. Academia can free film-makers from conventional narratives and forms, allowing for experiments in creative storytelling. But does their work impact in academia as traditional ‘research’ and what influence have their films in the broadcast industry?

Moderated by Hans Petch (Academic and Producer)

Participants: Nicola Daley ACS , Shreepali Patel , Joanna Callaghan (University of Sussex) and Susan Kemp (University of Edinburgh and producer)

Reflections on Sheffield Doc Fest by Anthony Martinez

“This will tell you the story of the exhibit.” I was handed a wireless mic pac with a short cord leading to a pair of noise-reduction headphones. “You can move freely to the different monitors whenever you want.” That was the end of my training but the just the beginning of my inquiry for the Sheffield Film Festival volunteer.

“What is the story here?”

On the ground floor of the Trafalgar Warehouse, the headquarters of all VR, AR, and MR demonstrations of interactive documentary storytelling, sits an exhibit on autism expressed through art in Japan. It’s tucked away in a corner that seems to narrow your field of view entirely upon approach. Of course, the trick is to assume its small and unassuming. It plays to the strengths of the exhibit when you realize the scale of its mission. Though, that still didn’t answer my first internal question, “What is the story here?”

Hiromi Kwj turns to me when she sees my face start to squint, “This is about autism in Japan.” Her comedic timing is never more punctual. Actually, she’s a helpful classmate, former resident of Japan, and an effective brain on nearly every subject matter in view or discussion. Four monitors play four different films, portraits, and scenes of a separate imagination of autism. The films are on rotary, each synched to different queues or narrative journeys. The first story was on a woman finding the rhythm of life through the music of performance art. She was quite beautiful. Her body moved with symmetrical precision, spiraling with grace in a counter-clockwise circle. Though, I was left to my own imagination what she was dancing to because my mic pack wouldn’t sync to her monitor. The sound of a slow, gentle voice matched its owner once I turned to the next film. The second monitor looped a short documentary on a mother discussing her son’s autism. Hiromi held her attention on this story in particular. It was a careful film. The kind only a sensitive director knows how to make. The cinematography, pacing, and overall mood were sincere, a reflection of the mother’s generosity and timidness. The camera frame stopped at her shoulders and only half of her face was visible to us. This allowed her to give her story to a person instead of a camera, which remained far outside of peripheral view. The music fades and the screen dissolves to black. It was at the end of the film that my thoughts returned to me and I remembered where I was standing. Funneled and squeezed into the corner of a ground floor warehouse, I was immersed in a topic and language I was equally unfamiliar with.

This was the strength of the exhibit in full force. There weren’t any light show, tangibles, or demonstrations. It was a corner of a room with four monitors and mic pac that worked for only one. Still, the exhibit breathed life and emotion with every new story presented. The third monitor played the most imaginative character of the lot and whose ideologies I will refer to independent research on one Ran Po.

Moving from left to right, the fourth and final monitor played the film I still struggle to interpret and whose impression has stripped me of the one I had hoped to leave with.

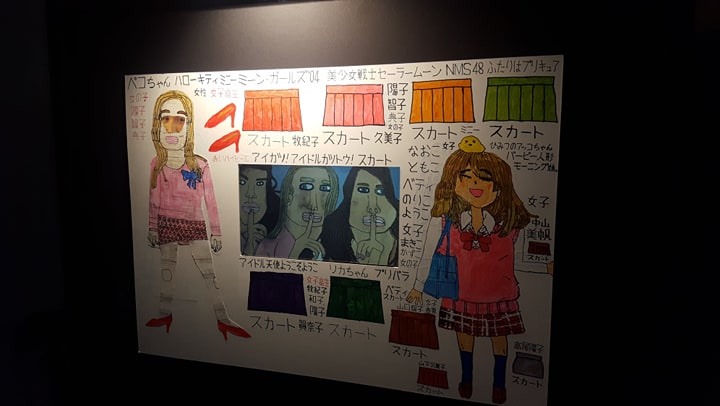

In short, two anime characters were displayed on opposite sides of a poster. Across the top, a row of multi-colored skirts were analyzed in single file. In the middle of the poster was a small cut out for a tiny monitor, which played a 30-second journey of the project and its creator, a man who also has autism. With the story being so brief, I could have done better to understand the project’s nature with subtitles or sound effects of some kind. Hiromi said it was about his interest in these characters and how he fancies their wardrobe.

“What did you think?” Hiromi asks. I take a moment to pause. I have a tendency to look away from someone when I think. A few moments pass and I turn back to Hiromi with the only answer I could find, “I think this was about giving feeling and not information.”

We return the mics and head from the corner into more open space. Another volunteer welcomes us, “Have you tried this exhibit yet?” I tighten a fashionable VR headset around my face and wait for further instruction. My eyes adjust to the sudden light change. The room is starved of all light and my thoughts being to roam free in the darkness. “Why did the mic only sync to one monitor?” My thoughts linger back into the corner of the room.

The Largest VR Experience in Sheffield

The headset engages with a series of scattered light. A pattern forms and I’m looking at the three other participants around me, each filled with a thousand corpuscles of light. They are all looking down at their hands. I bring mine up into view and share in their discovery.

I am standing inside one of the first exhibits on the ground floor of Trafalgar Warehouse. It’s one of the larger VR exhibits, both in world-building, prominence and scale of the message itself. Users or ‘viewers,’ (it’s still unclear how to name VR users) are loaded into a dark room, which eventually morphs into a nuclear launch silo. It’s one of the very few exhibits that takes a hard stance on an issue, a call-to-action for global nuclear disarmament. For me, the experience was solemn. I won’t go into many details but the staff and volunteers ask that you stay in one general location, taking an occasionally few steps to interact with a projected element. For anyone searching for a full VR experience, it’s important to note that you do not control the outcome or shape the story in any way. This doesn’t limit the experience, however. It just goes to show that some stories deserve to be experienced, rather than seen.

Speaking of experience, there are unsung heroes at every venue and exhibit scattered across town for this year’s festival. The orange shirt volunteers are the backbone of the festival. In the case of nearly every VR exhibit I’ve attended, they don’t shy away from questions or comments about the experience as a whole.

First-time VR users are highly encouraged to give this exhibit a try.

Virtual Reality Distribution: A Brief, Updated Summary

‘Experiences, not films’

There is no question that VR technology is taking center stage within the film industry and film festival festivals alike, as seen at the VR Distribution Conference in Sheffield Town Hall.

Positioning myself somewhere between involved and witness, I sit midway in the conference next to a looming granite column. I settle very quickly to begin taking notes, which pour into my Stickies Mac application without much interpretation of what the trouble is with current VR: “VR image is good, sound is bad. There’s a standardizing issue. It’s all open.”

The speakers are in the middle of listing the trouble with VR:

The headsets are not affordable and the sound is poor. There’s a non-standardization issue with what VR technology ought to share in its variations. For some audiences, VR is hard to watch more than 10 minutes at a time. Younger generations will grow up with different expectations and attachments to VR than previous generations. The trick is to put films into VR that are experiential and not just observable. The software takes a long time to boot up. You can’t fill a cinema with VR headsets because it’s time-consuming enough just to load it for one person. The software needs more investing. The reality is the VR experience is a slow render with a low-resolution playback. The achievements of working VR are astounding, but without attending an exhibition or upgrading your video game habits, you need to queue like the rest of us.

There is good news here, folks. In less than five years, the panelists project that VR will become globally accessible and affordable to households. The price of a commercially-profitable headset will fall with the rise of industry standards and competition for the largest market share.

VR is a rapidly evolving ’experience’ that is under ongoing debate as to the nature and direction of its use. Of course, the stories or films at play are not always interactive. For some, it’s just a great neck exercise. Still, the experience lies at the center of the debate. Should the viewer have a part in the film or simply update their standards of how a film can be experienced? I refer back to my first line of notes, “It’s all open.”

That seems to be the driving mantra behind Curzon Cinema’s push to make VR accessible to the public. They are the first cinema chain to research and fund VR headsets into their programming for what could be an untapped wellspring. We’ll have our answer in five years, I suppose.

The conference ends and I’m an unusually slow packer. My head is spinning with thoughts of the journey ahead and if our expectations as a public will be revealed by then. At that point, will filmmakers avidly pursue or anxiously disengage? The thoughts keep pouring and suddenly I remember that I’m positioned somewhere between being involved and acting as a witness. I refer back to my notes for some resolution to this post on VR and find an unusually strange tagline in hiding:

“It’s like we’re in the early days of cinema again.”

That’s funny. I don’t remember forgetting that was said.

Printing the Future

If you listen closely on the ground floor of the Trafalgar Warehouse, beneath the scattering ripples of inquiry, “What did you think? What did you see? How was it? Where to then?” There is a small ticking sound gravitating from its center.

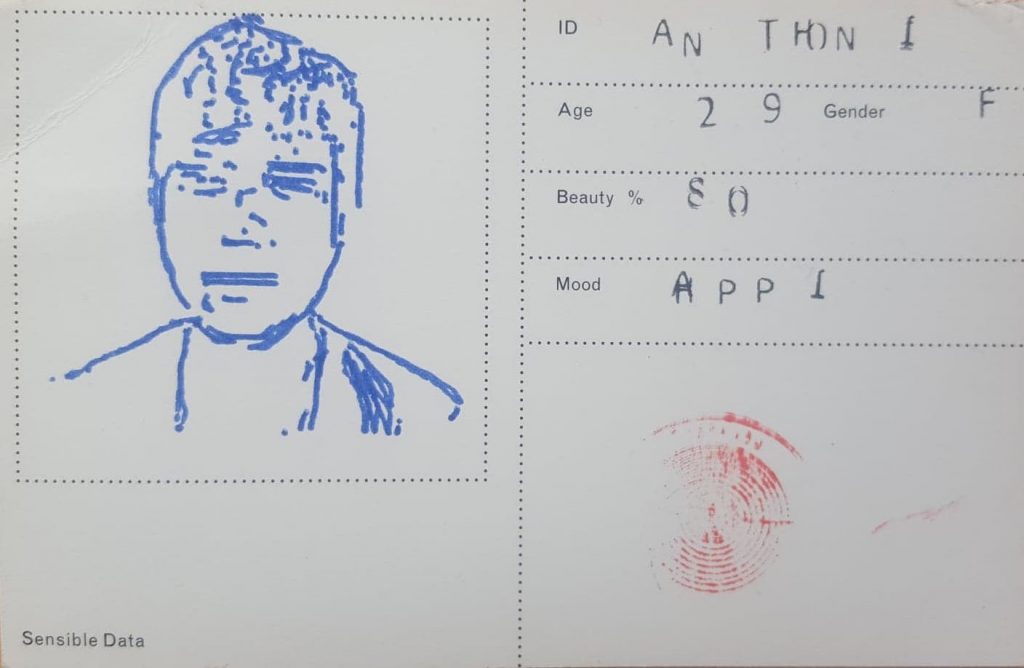

The culprit isn’t some jittery user excitedly bouncing a knee, or a timer reaching an end of a VR trial. It’s the sound of two tiny printers entertaining a group of three onlookers and two participants, at most at any time. The canvas is an empty small passport card with every related quality to an official one except for two distinct traits: age, gender, beauty, and mood.

See anything unusual in that last list? Most of the participants of the exhibit did as well. Yet, the focus of the exhibit was to show how the integration of algorithm-coded software with face-recognition technology could be used to predict a new set of qualitative values: image and likeness.

The results were varied I must admit. You begin seated at a table facing an iPhone which is synched to the algorithm. It takes a modest photo of you, assuming the algorithm detects sincerity. The photo then transfers to the first printer, one seat over, and begins plotting hundreds of drops of ink from a large blue pen. An image begins to appear. First the hair, then the eyes, and the final touches of a neckline. The passport is removed and taken to the second printer. The algorithm responds to the image and presents an interpretation of the aforementioned values. And then…

The results can be flattering. Your age could be younger or older, depending on which direction you care for. Your beauty score could be higher than you imagined. Your mood could be revealed to everyone, a promising token of artificial mood-analysis. What else can the future possibly hold, eh? Well, out of every technical feat this exhibit offers, of all the algorithmic wizardry in development of early artificial impressionism, against all odds, you would think it would identify some values better than others.

Apparently not. Antonita Reporting.

Photographs in Reflections are courtesy of Anthony Martinez and Hiromi.